Dragon Sickness

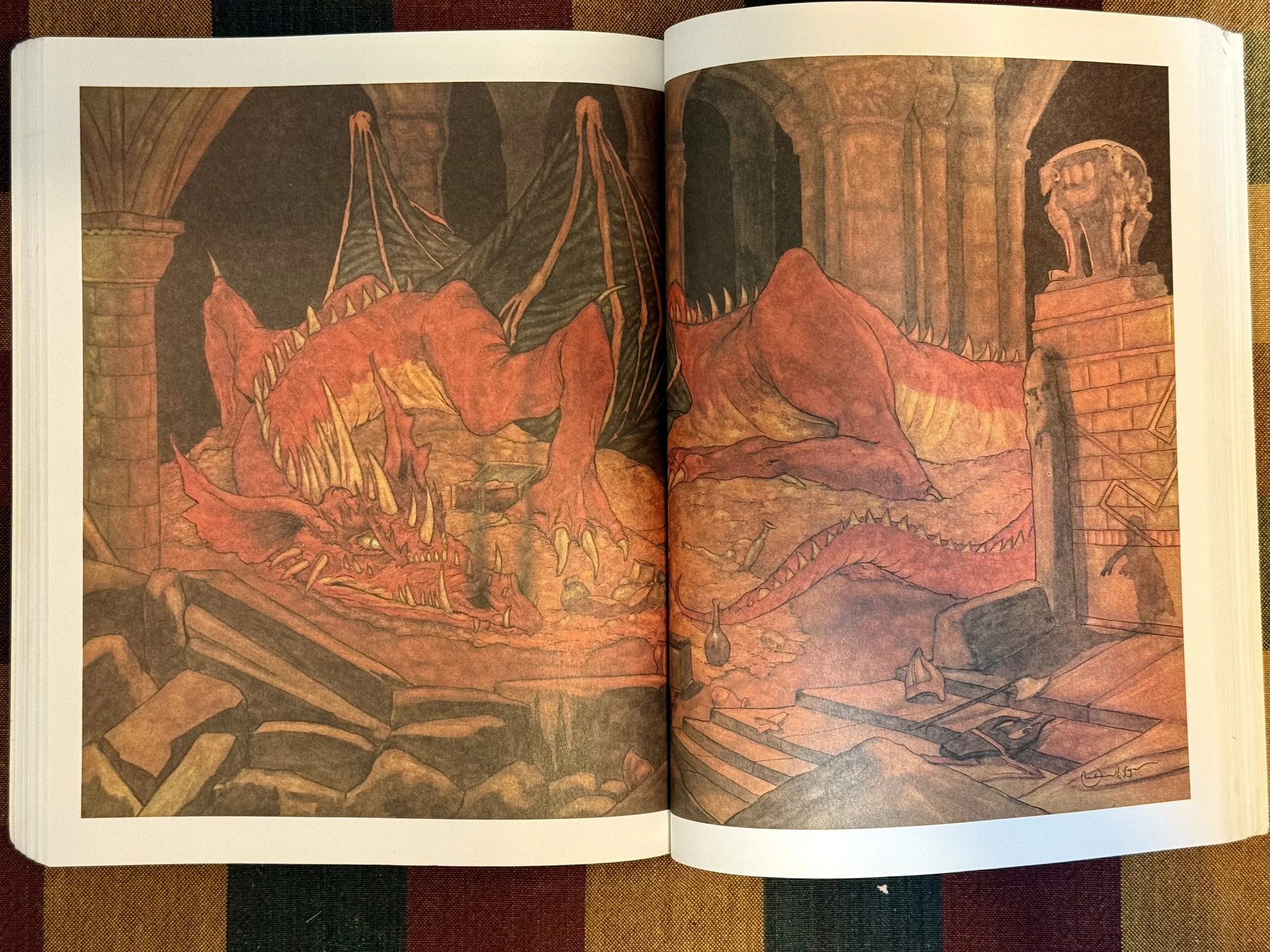

Image from The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien, Illustrated by Michael Hague

I used to collect dragons. Delicate resin statues, plastic toys with movable limbs, stuffed toys with cute faces—it didn’t really matter as long as they looked cool. I’d place them on shelves, my desk, or the top of my dresser.

I don’t remember when I started collecting them, but I really got into it when I worked part-time for a comic book store where dragon statues were abundant and marketed as “collector’s items.” I also don’t know how many I ended up with, but I know I bought more than I should have during a time I now wish I’d spent saving money (this was when I was living at home after college and not paying rent—I finally had “adult money” to do with as I wished).

Over this past weekend, I started the long and rather arduous process of purging my home of unnecessary possessions. It’s true what they say: you don’t know how much stuff you own until you try to pack it up or get rid of it.

It's not difficult to compare myself to the dragons I collected. In classic Norse and Old English mythology, dragons are hoarders of treasure that attack anyone who gets close. This is where J.R.R. Tolkien got the idea for Smaug from The Hobbit, and it’s where C.S. Lewis got the idea to make a parable out of Eustace Scrubb in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader.

Smaug isn’t using or spending any of the gold in the Lonely Mountain that he killed a bunch of dwarves to obtain. He’s lying in it, sleeping in it, guarding it against thieves (even though he himself is a thief). He’s the mythological manifestation of greed. In the second Hobbit movie, he proclaims to would-be “burglar” Bilbo Baggins, “I will not part with a single coin!” Thorin Oakenshield, the heir to the dwarf throne, takes back the Lonely Mountain and prepares to protect his kingly inheritance from interlopers. He then ends up with “dragon sickness”, which is basically just insanity brought on by greed. He becomes a cautionary tale for any leader seeking to get—and stay—rich.

Likewise, Eustace in his Narnian adventure encounters a treasure trove of gold formerly guarded by a dragon, imagines everything he could do with such wealth, falls asleep in the pile of money, and wakes up to the realization that he has turned into a dragon. It takes an act of Aslan himself to undo the spell and make him a boy again.

Image from The Voyage of the Dawn Treader

I don’t want any of that to be me. When I first started buying dragons to decorate my personal space, I called myself a “collector.” I convinced myself I was just expressing my personality as a lover of fantasy stories and themes. And in a way, I was expressing myself.

But I was doing it wrong. Instead of reading and thinking about and sharing the stories I loved, I was buying symbols of them to stare at. Instead of dedicating time to write my own stories, I was spending time working for money to buy an example of the thing I wanted to create. Why? Because it’s easier to buy something and set it on display than it is to live out your ideals or create something purposeful from them.

I became a coveter, not a collector. I was idolatrous; I had a mild form of dragon sickness that I’m still working to overcome. I internally hissed at any suggestion that I was accumulating too much stuff, because I had unconsciously tied my worth and identity to it, and my ego was sensitive.

Is collecting wrong? By itself, no. I’ve collected other things besides dragon toys, things that have genuine uses and help me fulfill my God-given purpose. For instance, I have a large book collection, for obvious reasons. I have a mug collection, which is useful for my tea-drinking habit or for showing hospitality. I also have a “fun word” collection in my phone’s notes app, which is great for maintaining my vocabulary.

But as I get further into adulthood, collecting—or at least, collecting without a well-developed purpose—has become less and less appealing to me. I can more easily see these days that my reasons for collecting have often been faulty. I was convinced that buying something new would make me happy or motivate me to act on dreams I was scared to live out. Or I thought that by trying to impress people with my stuff, like Skurge from Thor: Ragnarok, I could dispel my insecurities about my personal worth.

I’m done living like that. While some collecting has been beneficial, excessive collecting has done nothing but allow the same dust that rests on my dragon toys to rest on my soul.

This weekend, I was organizing and decluttering because I had a goal in mind: I wanted to find a book I bought several years ago that I haven’t finished reading, and I didn’t remember where I stored it (I haven’t had a decent bookshelf system in years, despite the fact I own plenty of shelves).

I opened box after box and discovered a bunch of collectible items, including dragons, that I’d just…forgotten I had. I thought, “If these things mean so little to me that they’ve been living in a box for years and I’ve barely thought about them, why the heck do I have them?”

Time is precious, and I only have the financial means the Lord allows me. I don’t want to waste either time or money on laying up purposeless, material treasure when there’s so much priceless, immaterial treasure to gather in this life through relationships, knowledge, and (hopefully) wisdom.